On Journeys

I have been giving a lot of thought to healing lately, and, specifically, to what this involves. While I have been focused on the emotional kind, I’ve felt inspired to think more broadly about healing arts.

There have only been a few moments in my life in which I’ve interacted with doctors, but they’ve all been instructive. Twice, an important machine evidently malfunctioned leading to talks along the lines of “I have bad news and good news. The bad news is you have 20 minutes to live.” And, then, after a long pause, “good news, sometimes it turns out the machine’s just broken.”

Another time, I’d been bitten very close to an eyelid by, I believe, a brown recluse spider whose family had been seen where I lifeguarded; and, after experiencing severe swelling, I needed to make a decision about whether to seek a doctor’s opinion despite this putting my place at a (beloved) religious summer camp in jeopardy. After going in anyway, I was told by a doctor “something sure bit ya,” before he informed me I didn’t need any medicine. I was relieved.

As an adult, I felt so much stress about getting engaged in my early twenties I experienced symptoms so worrying to me that I felt I should go to an emergency room. “I’m having trouble breathing and even feeling parts of a couple of my toes,” I explained. “Does that mean I’m having a heart attack?” After allowing it to sink in that it was actually possible for a person to know so little about medicine, the nurse on site informed me that, no, but had I considered yoga? (The toe culprit turned out to be dress shoes, but, again, I’d been healed of my fear.)

Why does it always seem to be one thing – be it a fear overcome, a greater expression of gratitude, an enlarged sense of self-respect, or even just increased mindfulness – that tips the balance toward healing, but that that one thing is almost always something new?

On Environment

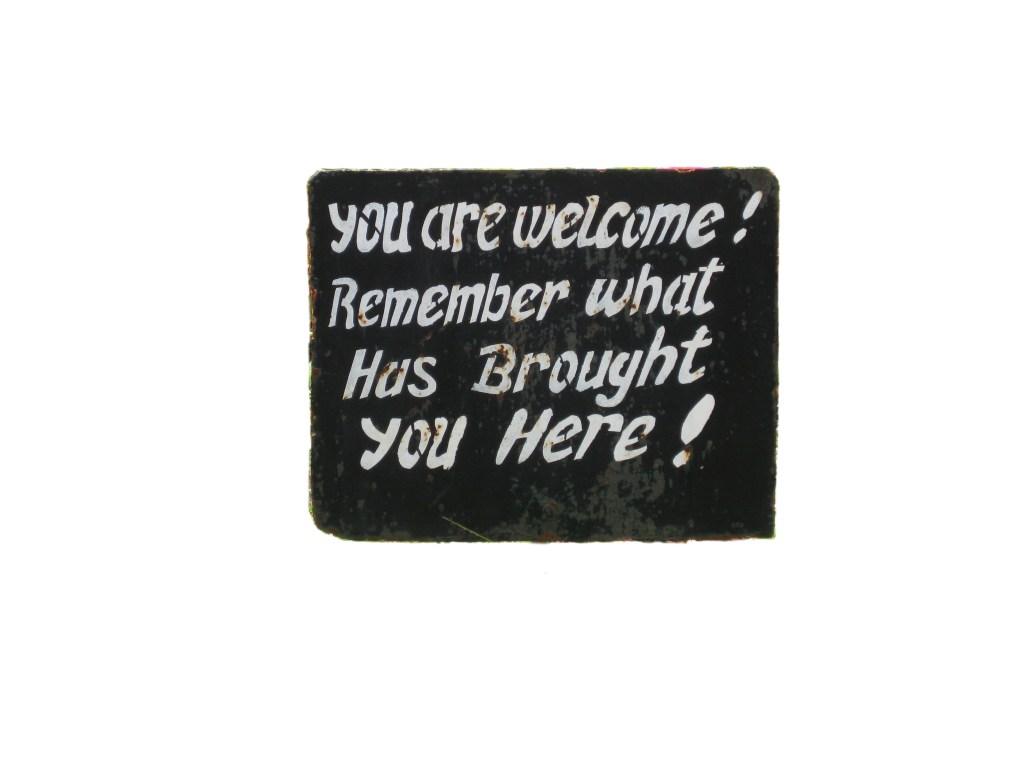

I love the sign highlighted above. During the approximately month-long period I spent in Africa – in Kenya, and, especially, in Uganda – one feature of daily life I loved most was a built-in multitude of encouraging messages – in an array of billboards, small talk norms, and even conversational tone. Like air and water, encouragement seemed to be very clearly recognized as a need everyone had; and, where I normally would have expected to see advertisements plastered, almost invariably, there were kind words displayed instead in order to help their readers enjoy a better day. And it felt wonderful.

Such environments, many times born of hardship (Uganda was recovering from brutal armed conflict), are particularly conducive to healing, and it is worth pondering why. I believe that, in addition to the obvious delight bestowed by handmade artwork where slick graphics are expected, the message these projects telegraphed was one of unequivocal inclusion.

On Citizenship

One of the most major challenges of trying to move forward with my life and career after experiencing hardship during my last years at CNN – and then talking about it – is that, as our media sector has become more large and, seemingly, power-hungry, it sometimes feels as if there is a danger of it overpowering any government, including our own; but saying so feels not only very discouraged, but risky. In many ways, since doing so anyway, without proper acknowledgment, I have almost felt like a citizen of no country.

If it is true that news corporations in a stock market economy have tended to serve as mixed shelters for the under- and over-confident in the absence of functional journalism, I still feel it will be essential that some entity hold these organizations accountable. And I still believe, regardless of what sorts of structural change our media infrastructure undergoes, it will be important to literally reverse the engines that have, largely, powered them and, rather than isolating and silencing those who have been hurt, listening to each one and applying lessons learned.

When I was little, one thing that was most memorable about observing life before and after a divorce was a sense of welcome in the world that seemed precarious.

But, in Atlanta, before becoming what does feel like a sort of refugee, I felt perfectly at home. Since my experience with the Larry King Live team, while I am grateful to have found more of an inner sense of home, I know more outward healing will be appropriate. But I am not entirely sure how.

I know I do not want to live where a group of over-domineering men capriciously decide who is and who is not a citizen based on the degree of personal fealty others display. (I’m only partly joking when I say watching President Biden fist-bump MBS this past week, I felt reminded of the experience of discussing ways of contributing moving forward with a news organization head around whom I’d felt terribly uncomfortable not long ago.) For all the public discussion there has been about gender equality in recent years, I’m not sure I know a single one of these men in very influential positions in media who does not appear to subscribe to a world view defined by what seems to be a belief that men should, as a rule, take credit for women’s intellectual contributions and that women should, as a rule, pay the cost incurred by men’s misdeeds.

But what is to be done?

On Mimicry

Critique does not seem to help.

Ralph Waldo Emerson once asserted, presciently, that “if you strike at a king, you must kill him.” Or else, he will begin to pantomime and parrot you, he may have added.

While my concerns about media are regarding both personal accountability and business models, I am focused largely on the latter, and I certainly do not wish harm to any individual. But sharing what I’ve learned in media – particularly with regard to a need for some form of counterbalance to protect against domination by the sector given its relationship to the stock market – and explaining how I learned it – felt important in both speaking up, and being heard, as part of the women’s movement. One of the reasons it felt so essential to do so several years ago now is that I was concerned that, in order to avoid culpability and calls for more principled business models, the industry may otherwise ignore such critiques just long enough to be able to entwine itself with a new social justice movement in order to call anyone opposed to its relationship with the stock market an opponent of the adopted movement. Two of today’s current conditions – that I do believe the media industry employed precisely the strategy I thought they would before critiques of their business model were allowed to be heard broadly – and that, despite what I do believe were wrong motives, this move actually did some good, advancing calls for social justice on several fronts – still, I feel, need to be addressed.

This is as I believe it is possible both to celebrate progress while insisting on its furtherance beyond the publicly-traded media model; and I strongly feel the dearth of entities willing and able to hold the journalism sector accountable for abuses of women’s rights matters. A lot.

On Parameters

I often wonder, am I correct that journalism corporations’ ability to issue and trade stock may be ultimately be considered unconstitutional?

If the Declaration of Independence establishes that the intent of our Constitution is to protect life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, a balance between our rights to be safe, free, and reasonably informed was also intended; and, because both the Declaration of Independence and Constitution were written before the establishment of any American stock market, it is fair to assume that, while the specific overlapping effects of an allied stock market and publicly-traded journalism sector were not foreseen, they do arguably systematically interfere with Americans’ already-recognized rights, thereby throwing off an intended balance. Our current media infrastructure’s funding mechanism could be considered almost like a tapeworm – not only failing to provide, but sometimes seemingly even taking away, what is absolutely essential. And one challenge that has arisen from the addition of cancel culture as a remedy is that, even though personal responsibility matters, when substituted in excess for the removal of the systemic problem, like a vitamin that is not water soluble, it seems to have toxic effects.

While I could potentially understand an education sector insisting temporarily on restricting civil debate in an intellectual landscape within which people are woefully uninformed with training wheel-like guidelines for dialogue, so long as it were working on – rather than concealing – the root of this large-scale uninformedness, the journalism sector currently in place is arguably more akin to a bicycle training stand, sometimes more effectively harnessing citizens’ emotional work for its own profit rather than forward movement for the country. But Americans are citizens.

If it is true that practically all forms of large-scale and organized resistance to the adoption of just initiatives are composed of two parts – profiteering ring leaders and a conglomeration of followers either unwilling or unable to stand up to them – it is in the exposure of the former group that the latter is freed.

The good news is that, as Americans, we are equipped with a roadmap to healing.

On Sequence

Another reason I believe it may make sense for a media ecosystem currently powered by the profitability of addictive and pain-killing ratings and rage, thereby incenting problem-avoidance and problem-creation, to instead be fueled by the benefits rendered by nourishment and problem-solving itself, is that, through system redesign, funds paid to journalism providers could be increased and distributed based on merit, resulting in a more sustainable business model for everyone.

The unhelpfulness of the rage model is one reason I believe debates surrounding questions of hotly contested topics can be so unhelpful. At the points where public affairs dialogue is concentrated, voters’ perspectives tend to have diverged long before; and it’s at this point of divergence, it at least seems to me, where dialogue needs to begin. (Javert and Jean Valjean arguably needed to know more about one another’s hunger – both material and spiritual – before understanding their respective situations helpfully; and real-life analogues seem to persist today.)

On Purpose

I very briefly got to know a doctor several years ago and, as personable as he was, he spoke so insensitively one day about needing to pop into the hospital in order to drug up his patients real quick that, without realizing it, I began to lose respect – not only for him, but for his profession. I started to wonder whether, too often, its leaders viewed people as little more than addicted and out-of-touch sources of profit lacking in inherent value.

I had barely given this a second thought before, several years ago, I needed to face the possibility of having a surgery. Having prayed with satisfying results about so many topics over so many years, I believed that, in prayer, I would see this need disappear; but it persisted.

Feeling certain God could take care of it, I prayed more. And prayed. And prayed with another person.

I remember wondering why will this problem not go away? Am I not doing what I am supposed to be doing? But, it felt right to go and have a procedure done (and, I should note, I was also encouraged to do so by the person praying for me); so I did.

Almost all I remember about this experience were the nourishing qualities of compassion, welcome, and genuine – undeniably genuine – kindness expressed by the nurse who welcomed me. Any negative assumptions in my heart about the whole of her field were healed totally from this perspective. Afterward, I was physically healed as well and felt ridiculous taking the needless painkillers her colleagues had handed to me. So I threw them away.