So, my saga learning from the surprisingly dramatic survival strategies of local birds along my running route continues. This past week, and still feeling inspired to consider having witnessed a gorgeous robin seem to change his or her mind about feasting on a little worm as a sort of wink from the universe in acknowledgment of all the thought I have been devoting to the idea of coexistence in a spiritual sense, I felt absolutely awful about having approached another member of the species who’d just made a valuable catch, but, distracted by me, lost her or his little treasure to an opportunistic neighbor who snatched and flew away with it in barely a blink. The bird looked and even sounded exasperated by my interruption, I felt anger at myself, and I identified with the bird.

Later, however, I was relieved to observe a similar attempt thwarted as a quick-thinking third worm hunter opted to steal away with her or his lunch under a car and it got me thinking. I don’t know about you, reader, but it seems that, for me, lessons I am seeking to learn show up wherever I happen to be so often they feel important take pause to consider.

This past week I also enjoyed watching a recent interview of President Biden anyway in which he talked movingly about having weathered and learned from one after another enormous loss.

It is almost astonishing, really. How many times can seemingly vital supports be removed from a person so devastatingly and so suddenly without destroying his or her ability to remain upright and to proceed? Every time I hear of a story of a severe or repeated heartbreak handled, it becomes a little bit more natural to feel confident each can be turned around and used for good. And I feel this has clearly been illustrated in the example of resiliency set by our president.

But it felt important to recognize how qualified this feeling of hope must be when hearing a popular author, just afterward, compare the decline of a series of historical societies with the state of our own today, although he did not offer many possible solutions. And I’ve been pondering what additional lessons may be gleaned at what some seem to believe may be the possible end of our nation as we know it by revisiting decision points encountered at the country’s founding. What so far-unseen parallels may there be between our current predicament and other ones that seemed intractable at the time of America’s founding but that were, ultimately, resolved?

While I realize it may not appear an obvious analogue, I’ve been struck lately by what seem to me to be a number of similarities between the dilemma such preeminent figures as former presidents Thomas Jefferson and George Washington faced in talking through modes by which the institution of slavery could or would be extinguished in America (Jefferson, a slaveholder, having argued for a deliberate phase-out and Washington, another slaveholder, having opined that the practice would die out on its own, I believe) and the problem of addressing the institution of the stock market in America today.

Of course, it certainly seems to have appeared in the case of the former that, in the absence of broad consensus amongst the founding fathers and their peers on the topic, resolution needed to be delayed, the idea of the country’s founding having been recognized as being too big to fail. (I’ve felt reminded, as well, recently of the obviously very different dilemma the Obama administration faced in buoying big banks in response to the financial crisis of 2008 as, while not fully acknowledged, it still seems to me this was a case in which a major structural problem with the country’s economic system, rather than being addressed in a thorough way, was, too, kicked down the proverbial road.)

We all know how the scourge of slavery was finally addressed in the U.S., with devastating and traumatic war that, finally, forced the end of race-based involuntary servitude in America. And a nationwide dialogue about the effects of an unaccountable stock market sector on the country’s well-being has, so far at least, simply been prevented.

On false choices and debate-flattening

When I was little, the church my family attended was founded by the Pilgrims (the congregation’s first services having been held on the Mayflower), and visiting Plymouth Rock, too, on Sundays felt like proof of the relatedness of these devoted pioneers’ purpose to our own today.

What sustained the Pilgrims, in addition to the obviously almost miraculous kindness of the Native American Wampanoag, seems to have been a reliance, rather than on any particular person or organization, on principles. And this is one reason it seems to me that opportunities to protect what should be cherished about our country from corporate cooptation seem to be falling on after another. To the degree that any person or group who stands up to corporate media, however valiantly, does so in their own strength, each seems so vulnerable.

Just as I did in Paper Parks, I believe it still essential today to point out that credible does not mean infallible. It is understandable, of course, when people celebrate apparent societal advances, whether such change is (or looks like it is) driven by organizations or individuals. But, as I wrote in 2019, I believe the danger in such scenarios is in a resultant tendency to lean on such organizations and individuals. I’ve hesitated to write about other individuals on my webpage, but I feel it important to address the roles of activists like Bari Weiss, given how aggressively she and her organization at least appear to have been about engaging with my work so furtively in recent years even while not engaging with me at all. Even though she had already amassed a large television audience by that time, I did feel courage was expressed by Ms. Weiss in leaving her role with the New York Times and that this courage implied a measure of credibility. That said, I believe this courage only addresses one of the three main ingredients that may be most helpful to consider in media sector reform, the others being candor and creativity.

While I do not listen to it now, I did hear to some of Ms. Weiss’s early podcasts and appreciated her candor then in expressing to celebrity Kim Kardashian an aspiration to also become an influencer. But I feel this transparency was downgraded to a degree when, in naming the next generation of Ms. Weiss’s publication, the term “press” was employed. If it is true that an “influencer” is a sort of self-selected, and certainly unelected, politician, this is distinct from the definition of a journalist to the degree that the modern influencer gains wealth and a following by continuing to use the term journalist while shaping the views of unsuspecting followers primarily through an undisclosed practice of journalism suppression.

While the suppression of information and ideas may seem expedient in the short term, I wonder whether the resulting flattening of debate is more to blame for the chronic misunderstanding and polarization that seems to be plaguing the country than tends to be readily acknowledged. Such debate flattening has seemed to compel citizens, for example, to choose between the idea that there is no such thing as unjust discrimination and the idea that all standards are somehow unjust, or imagine it’s so likely their only good option is to be ruled by an increasingly dominant media sector that it would be unwise to wonder whether there may be a better way – we’d better not even think about it, in fact.

Strong media organizations are, of course, part of the solution to the problem of polarization facing the country, but I do not believe such organizations alone are going to do it.

As a person who spoke up about proposed solutions during the women’s movement in corporate journalism, I continue to feel it should be noted that the BlackRock-sponsored investment firm Blackstone arguably didn’t recently buy the country’s premier (and, crucially, rendered premier artificially through self-selection and the suppression of contributions from the women in corporate journalism, I felt, it purported to represent) woman-focused production company in order to invest in the women’s movement in corporate journalism; it bought the company in order to stop the women’s movement in corporate journalism, and the why needs to be seen.

While I, relatedly, by no means believe the political prosecution of Donald Trump qualifies him for re-election any more than being descended from a person who has experienced injustice would alone automatically qualify a person for a leadership position, it still seems to me fair to try to talk about what he is experiencing accurately in order to help avoid misunderstandings as I believe it may be the suppression of journalism by large organizations like CNN and even smaller ones like the Free Press alike that the very conspiracy-minded thinking and tendency to scapegoat that they complain about is happening at all. (I feel there are strong parallels, so far unarticulated, between an arguable tendency of start-up governments to scapegoat and abuse large swaths of their populations on the basis of race and ethnicity and an arguable tendency of struggling organizations to scapegoat and abuse large swaths of their own constituencies on the basis of sex.)

To simultaneously characterize the past several years of corporate social justice activism as a “revolution” while keeping the public in the dark about what it almost certainly has been – a serious game of broken telephone set into motion by corporations concerned about their ability to continue issuing securities without better centering concepts of equal opportunity after this was called into question – even if well-intentioned, is arguably irresponsible at best as keeping people in the dark while encouraging them to panic is almost certainly never advisable.

The corporate media military industrial complex is a system, not a person, and just as it is not ultimately led by any individual like Bari Weiss or even Mark Thompson, I am not sure its solution will be found in just one company or even a collection of them as it’s the system’s structure itself that needs further consideration.

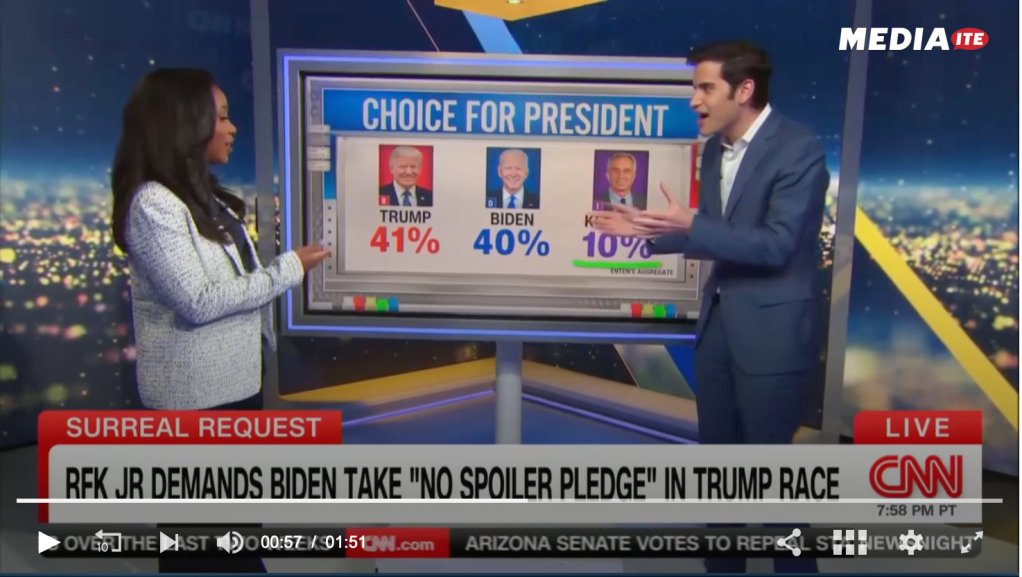

Our country was designed to derive its authority on principle and to be able to stand on its own. And, at a certain point, such structural aides are a hindrance. It felt jarring to hear a CNN clip recently in which an RFK, Jr. press conference that emphasized so-called battleground state polls was summarized, I felt, inaccurately by an anchor who critically implied the candidate’s message only addressed national polls.

Could the solution be to separate journalism & stock market?

We still need to confront – out loud – the almost unimaginable recklessness of our country’s willingness to allow such sectors as journalism, pharmaceuticals, and weapons manufacturing to become infested by relatively unaccountable stock market forces that seem to continue to distort practically every facet of American life, pitting people who could be friends against one another even while the so-called “overton window” of acceptable conversational topics shrinks and widespread frustration, as a result, grows.

What have been considered, in recent history anyway, to be the so-called golden handcuffs of corporate endorsements have, in my view at least, morphed into something much more like training wheels, or, even more accurately, children’s arm floaties on a grown man tasked with the responsibilities of a lifeguard: accoutrements not of diminishing, but of demonstrably negative, value.

Television news corporations arguably hold far greater influence over the country than any branch of government (I was discouraged but not totally surprised to learn recently that big pharmaceutical corporations tend to spend more money on tv ads than the armies of lobbyists often blamed for the formulation and passage of harmful health policies), and I think this is increasingly understood, even if not acknowledged.

But I feel it may be important to underscore how this influence is pooled and wielded and why this relates to ways in which the now-largely corporate democratic party’s efforts to focus on the country’s past faults more than its present strengths, as well as what has seemed to be much less of a renegotiation of the concept of federalism to include corporate interests alongside national and state legislatures than an intentional national suicide meant to destroy the country’s self esteem and populate it with people so grossly uninformed and mysteriously bankrolled by dollars that seem to be worth less with every passing month that they are easy for mindless corporate profit-maximization machines to control. Not a regime change at all, in other words, but regime removal with no plan for the future.

But what if the answer is, rather than a sweeping change, something small and doable?

I do not know whether the disentanglement of the stock market and news funding would, as seems to be a possible fear, ultimately end the stock market altogether. Just look at the effect even the questioning of the legitimacy of stock market-traded corporations has seemed to have over approximately the last five years: the speed and nimbleness with which they have transitioned to championing concepts of social justice with regard to ethnicity in public has been almost breathtaking. Of course, one problem with this response, in addition to its arguable narrowness, has been its lopsidedness, the United States having been founded on the primacy of the dual concepts of freedom and equality and liberties like freedom of speech do seem to have been grossly deprioritized.

But this is yet another reason for a national dialogue on the topic of the overlap of the stock market and corporate news sectors: Moving forward, corporate America cannot be held to account by one or even a few anonymous agitants but must, I believe, be counterbalanced by a legitimate journalism sector.

This is why, despite the significance of the problematic nature of corporate influence over for-profit weapons manufacturing, big pharma, and big agriculture raised so often by independent thinkers like presidential candidate RFK, Jr., I believe the prioritization of the link between stock market forces and the funding of the journalism sector may be most important to address as a restored journalism sector would, arguably, automatically begin covering the other subjects, prompting, one could imagine, a reversal of the rot currently eating away at our economic system by getting at it at the root.

I am not sure whether the overlap of stock market and corporate news forces can be severed legally (although, actually, I believe it could), but even if this proves impossible, an electorate that is simply informed about the relationship between these sectors could reasonably be expected to turn to other journalism sources.

As I wrote at length in 2019 in Paper Parks, I believe that the corporation as a means through which we as a populace can gauge the degree to which founding principles like freedom and equality are being upheld could conceivably be a helpful lens. But only with an optometrist to modulate its strength. Corporate America’s imprecision requires just as much attention as its precision in addressing social justice ills, and without a journalism sector to hold Wall Street accountable, corporate entities are arguably worse – if not far worse – than useless. Absent a bulwark against unmerited corporate dominance, Wall Street and corporate media tend to align in a treacherous sort of gimbal lock in which they intentionally neglect the work of journalism itself in favor of self-serving narrative formulation.

Today, what is termed “wokeness,” I believe, has intentionally been warped to conflate legitimate and illegitimate concepts in order to stoke division and, in the modern media sector at least, is not always about a genuine alertness to injustice at all. It is an appearances-focused self-preservation strategy that is much more about pandering, bribery, and whitemailing arguably meant to prevent dialogue about whether a transition from democracy to rule by media organizations has been wise at all and whether the journalism sector’s relationship to the stock market needs real public consideration and scrutiny.

I believe that if they considered the topic deeply and in an informed way, most people would agree that the stock market – an apparatus that would fuel the U.S. economy with a gambler’s mindset and coldly speculative posture – is an immoral institution absent a journalism sector to hold it to account. But it is an institution deeply embedded in our economy in which an enormous number of Americans are invested, and it has lent enormous support to many presumably well-intentioned politicians.

An unbridled stock market system is arguably to blame for many of the world’s problems, including global warming, the obesity epidemic, numerous forms of malnutrition, so-called forever wars, widespread addiction to pharmaceuticals, the whittling away of the middle class, and many others. But not only do I not believe we should phase out the institution overnight, I am not sure when it will end altogether or whether it is simply our task to consider means by which it can be disentangled from the journalism sector. Might this not be an issue that could help bring at least some of the country back together?

I empathize with the Biden administration. Like Thomas Jefferson and George Washington before them, they are also deeply entangled with an economic institution that arguably needs to be addressed urgently. (Thank goodness the relocation of the American capital from New York to Washington was negotiated just two years before the NYSE’s founding.) Not only do I believe that this problem is what the 2008 economic crisis, the so-called Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street movements, as well as the election of Donald Trump in 2016 and subsequent riot in 2021, were really meant to address, but it often feels as though this possibility has not been given needed consideration as discussion of the merger of the Wall Street and journalism sectors is uniquely censored and suppressed. Even so, I by no means believe that, like the institution of slavery, the stock market’s relationship to the news sector will need to be addressed so adversarially in order to be resolved.

I do not know for sure who should be the country’s leaders moving forward. It may well be that the Biden administration is meant to hold onto its position another term. But the simple fact that discussion of the intersection of Wall Street and corporate news has been suppressed so aggressively shows, I believe, that it needs to be discussed at some point at the national level. Maybe if the Biden administration were more informed it would make a strong case for the examination of this nexus (who knows?), but it seems to me that the presence of an independent candidate today who has clearly demonstrated a willingness to talk about such topics may be a more compelling reason for hope on the subject and, to me at least, feels almost like a twice-in-a-lifetime opportunity (the MeToo movement in corporate journalism having been the first) to raise an issue that I believe deserves urgent attention.

I’ve enjoyed further considering the wisdom of the robin who, rather than getting angry at me for being a distraction or angry at his or her fellow bird for being an attempted robber, was simply ready to move when needed in order to prevent injustice ahead of time.

It’s so important, I feel, to remember that the answer is not to be angry at another person. I’ve loved learning about the idea that there is no such thing as private innocence and that, while none of us, as human beings, has it (definitely not me), in Christ we are innocent and complete. And we are equal partners. On the topic of media sector reform, I realize mine is one opinion of many, but, regarding the division facing our country today, it still feels important to underscore how valuable it may be for us to be talking about systems.

In contrast with the training wheels we all need to lose, there are some structures we should cherish. Anyone who has ever experienced heavy loss – the kind that doesn’t feel like the removal any sort of external support but more like some kind of surgery that would steal the very marrow out of your bones – (like both President Biden and RFK, Jr. and countless numerous others, by the way) knows it’s to be avoided if possible. I re-listened recently to The Gutter Twins’ Belles and think Mark Lanegan said it best: feels like forever once it goes away. While I realize it may seem silly to wax poetic about something as seemingly impersonal as public policy, the principles on which our country was founded are valuable and worthy of protection.

Even though I have long believed a national dialogue about the relationship between stock market forces and the news sector in American life is needed, I’ve felt tormented by the question of whether it is time for such change. How disruptive would addressing the problem be? But I actually don’t know. Not to reference too many songs in one post (I revisited an old painting mix), but James Blake’s call for some sort of forest fire continues to resonate. (Let’s just let it be a controlled burn.) Steps forward, regardless of size, are most sustainable when made at the right time and in the right order, of course, and this maxim scales. And I feel that, as a country, we need to be at least ready to tackle this issue and that the way to be prepared to do so is to talk about it more. I do not believe it’s too early to do this given the way corporate America already seems to have begun eating our lunch.